The Center for Biological Diversity notified the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Thursday that it would sue the agency for failing to protect the birds under the ESA if it did not do so within 60 days.

The delay is not good because it creates uncertainty, said Wayne Walker, CEO of LPC Conservation, the only private conservation bank for the lesser prairie-chicken in the bird’s range, which includes western Oklahoma.

Conservation banks work with landowners to preserve habitat needed to save species in danger of dying out while allowing essential economic drivers to continue development.

“They (landowners) get what they need financially, and the bird gets what it needs,” Walker said.

Dancing grouse has primal connection to the land

By: Kathryn McNutt The Journal Record August 12, 2022

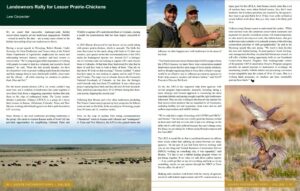

The lesser prairie-chicken not only matters as an indicator of our environment’s health. It forms a primal connection to the land and its inhabitants for centuries.

It needs space and protection: Ideally, a lesser prairie-chicken needs 25,000 contiguous acres of appropriate habitat to meet its breeding, nesting and brood-rearing needs to thrive.

Stephanie Manes, a research biologist with LPC Conservation, works with landowners like Gardiner Angus Ranch in Ashland, Kansas, to bank grassland for a permanent conservation easement that can restore the bird’s dwindling population.

Survival of the species is important both environmentally and culturally, Manes said.

The bird is the top indicator of the ecosystem’s health and, as the largest upland game bird, fed humans for hundreds of years, she said.

Last, but certainly not least, the lesser prairie-chicken “is one of the most charismatic birds,” Manes said.

The spectacle of the males’ elaborate mating dance has captured the imagination of people for centuries.

Oil industry prepares for restrictions to conserve rare bird

CARLSBAD, N.M. (AP) — Lesser prairie chickens once numbered in the thousands throughout the American West, thriving on the prairielands of eastern New Mexico and the American West.

But in recent years, the chicken’s numbers declined amid growing development in the oil and gas and agriculture sectors, and conservationists worried the unique bird could be in danger of extinction.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed federal protections for the species last year under the Endangered Species Act, seeking an endangered listing for the bird in southeast New Mexico and West Texas and a threatened listing in the rest of the animal’s range, which extends through Colorado, Oklahoma and Kansas.

A species is considered “endangered” by the agency when its extinction is believed imminent, while “threatened” means the animal could soon warrant endangered status. Both result in the federal government developing a recovery plan and setting aside acreage deemed “critical habitat” of the species at risk.

A final decision on the lesser prairie chicken’s listing was expected this month, records show, and it could restrict access to lands needed for the chicken’s recovery and impact some of the region’s biggest industries.

USFWS approved range-wide habitat conservation plans for lesser prairie-chicken

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently announced it has approved range-wide habitat conservation plans to provide legal assurance of compliance with the Endangered Species Act for the lesser prairie-chicken for the oil and gas industry.

The USFWS approves conservation banks that meet quality standards defined by guidance published by USFWS for the LPC in July 2021.

The habitat conservation plan is designed to allow for the responsible development of oil and gas in the Great Plains while also contributing to the conservation of the lesser prairie-chicken, the agency said.

The Endangered Species Act requires all incidental take permits to include HCPs that describe the anticipated effects of a proposed taking and how those impacts will be minimized or mitigated.

The HCP will cover oil and gas development across the lesser prairie-chicken’s range in Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, the agency said. LPC Conservation LLC’s HCP will fully offset impacts from enrolled projects while providing regulatory certainty for oil and gas development across its range, should the lesser prairie-chicken become listed under the ESA in the future.

Along with the final HCP, the USFWS is publishing a final Environmental Assessment that evaluates the effects of issuing the ITP and addresses comments received during the public comment period. Full implementation of the HCP is expected to potentially affect 500,000 acres of suitable lesser prairie-chicken habitat. Under the plan, industry participants will work with LPC Conservation LLC to ensure projects minimize impacts to the lesser prairie-chicken and mitigation is in place to voluntarily offset their project’s impacts to the species and its habitat. The HCP and ITP will be in effect for 30 years.

Earlier this year, the agency approved LPC Conservation LLC’s HCP and associated ITP for renewable energy development in the Great Plains.

Service Approves Lesser Prairie-Chicken Habitat Conservation Plan for Oil and Gas Development in the Great Plains

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has approved LPC Conservation LLC’s habitat conservation plan (HCP) and associated incidental take permit. The HCP is designed to allow for the responsible development of oil and gas in the Great Plains while also contributing to the conservation of the lesser prairie-chicken.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) requires all incidental take permits (ITPs) to include HCPs that describe the anticipated effects of a proposed taking and how those impacts will be minimized or mitigated.

The HCP will cover oil and gas development across the lesser prairie-chicken’s range in Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. LPC Conservation LLC’s HCP will fully offset impacts from enrolled projects while providing regulatory certainty for oil and gas development across its range, should the lesser prairie-chicken become listed under the ESA in the future.

Along with the final HCP, the Service is publishing a final Environmental Assessment (EA) that evaluates the effects of issuing the ITP and addresses comments received during the public comment period. Full implementation of the HCP is expected to potentially affect 500,000 acres of suitable lesser prairie-chicken habitat. Under the plan, industry participants will work with LPC Conservation LLC to ensure projects minimize impacts to the lesser prairie-chicken and mitigation is in place to voluntarily offset their project’s impacts to the species and its habitat. The HCP and ITP will be in effect for 30 years.

Earlier this year, the Service approved LPC Conservation LLC’s HCP and associated incidental take permit for renewable energy development in the Great Plains.

To save it, list the Lesser Prairie Chicken as endangered

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is scheduled to announce its final decision on whether to list the Lesser Prairie Chicken as an Endangered Species under the federal Endangered Species Act in June. If FWS chooses to list this species, it would mandate the designation and protection of critical habitat, put criminal penalties in place for harming the bird, and require industry to mitigate any negative impacts they have on the species.

If we have any hope of saving the Lesser Prairie Chicken from extinction, then listing the bird as endangered is essential. While states like New Mexico have worked hard to turn the Lesser Prairie Chicken situation around, unfortunately results matter and, as all ranchers know, you don’t put food on the table with effort. It takes results, and current and past efforts have not delivered them. Since formal nationwide bird monitoring began in the 1960s, Lesser Prairie Chicken populations have declined by 97% across their range. This decline is one of the most precipitous among all bird life in the U.S. and will ultimately lead to extinction if not addressed.

Ensuring the future existence of this bird will come at a cost. In the limited areas where the species remain, they require a wide-open prairie landscape devoid of vertical structures – e.g. trees, power lines, drilling rigs, etc. – with healthy stands of native grass and forbs. Both fossil fuel and renewable energy production are incompatible with the habitat conditions these birds need, as is the overgrazing of livestock – meaning these activities will have to be curtailed in the areas designated as “critical habitat” for the bird.